Can Libya’s Oil Industry Make A Comeback In 2021?

The creation of Libya’s interim government has instilled the international community with tacit hopes of a decade-long conflict finally coming to an end. As it is oftentimes the case with Libya, aspirations remain alive only insofar as they are not accompanied by deadlines to be met. The interim government has a little less than 2 months to “create the constitutional basis” for the Libya’s first democratic elections of this century (assumed to take place in December 2021). The complete unpredictability of what is going to happen next has been delaying much-needed investment into Libya, with most investors (even those who happen to have equity) fearing another landslide into all-out mayhem is still on the cards. Against all this, Libya has been trying to struggle its way through another round of plummeting differentials.

The force majeure, initiated mid-April by Libya’s NOC that debilitated operations at the Marsa el-Hariga Terminal (loading Sarir and Mesla grades), took less than 2 weeks to overcome. AGOCO, the NOC’s fully-owned upstream subsidiary, claimed the Central Bank of Libya (CBL) did not transfer its income in due time – reportedly not a single Libyan dinar since September 2020 - compelling the firm to wrap up operations. It took CBL exactly one week to wire 230 million USD to AGOCO’s account and within several days the port of Hariga was loading cargoes again. By early May all fields connected to Marsa el-Hariga were reported to be running at peak capacity. This, of course, does not eliminate the risk of further disputes, especially on highly contentious issues like reporting oil revenues where the underlying causes of discord remains simmering under the surface.

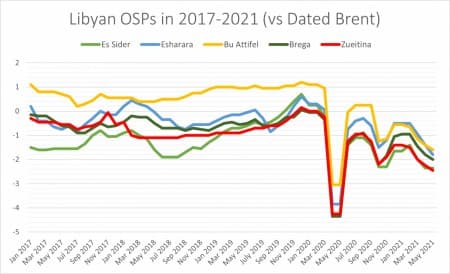

Usually Libya’s NOC issues its official selling prices (OSP) for the upcoming month on the last week of the month preceding the loading. For the second time already this year, it had delayed the OSP issuance into the actual month of loading, taking roughly a week more than it generally should. Following the market ruckus caused by the force majeure, NOC probably wanted to wait for the mayhem to abate. Still, it was induced to decrease prices even further, especially the light sweet ones. El Sharara suffered the most marked depreciation month-on-month, dropping 40 cents to -1.8 USD per barrel against Dated. Smaller flows like Brega, Bu Attifel and Zueitina were hiked by 20 cents per barrel; all the other grades saw insignificant month-on-month changes or were just simply rolled over. Interestingly, Sarir and Mesla, the two grades that have suffered from the force majeure, were also left unchanged.

With Libya’s largest crude flow - Es Sider - lingering at its lowest differentials ever, Libyan energy authorities are closely following the intense competition with incoming US grades as well as Mediterranean peers such as CPC or Azeri, hoping for their influx to ease. This might well be a pipe dream, at least temporarily, considering that US crude arrivals to Europe in May 2021 are at their highest since September 2020 and the tally might still edge higher from its current level of 24 MMbbls (the sailing time is usually 18-20 days so the final number could only be assessed mid-month). In addition, the gradual winding-down of OPEC+ production quotas has lifted crude production rates (just to name one example from the ranks of Libya’s competitors, this year’s CPC output target is 150kbpd higher than in 2020, at 1.44mbpd) and the wide Brent-Dubai spread has killed off most of the previously existing arbitrage opportunities.

Hypothetically, Libya could channel more crude into other streams and thus optimize its revenues by placing more emphasis on crude streams that it believes to hold higher value. However, for this happen Libya would ideally need the liberty to choose which plays or deposits it would prefer to develop; that is hardly what Tripoli has now after 10 years of fratricidal conflict. Perhaps unfortunately for Libya’s NOC, a significant part of Libya’s prospective fields to be commissioned will be channeled into Es Sider flows – the Dahra and Bahi fields are currently being refurbished and will bring in some 20kbpd once they reach their assumed plateau at some point later this year; North Gialo and Gialo III (the two combined have a nameplate capacity of 150kbpd) might take several years to launch but should bring the total Es Sider flows to 500kbpd.

Thus, Libya has found itself in a limbo whereby the short-term prospects of its oil industry ultimately depend on not just one but several key factors. These can be categorized along the following dilemmas:

- could the interim government manage to navigate Libya to an election without new flare-ups of fighting?

- will light sweet differentials improve over time so that Libyan grades garner more?

- when will the arbitrage towards Asia reopen and how long would it last?

The most important point of agenda, of course, is the political unity of Libya – without it the Libyan NOC will not be able to breathe new life into exploration drilling and to allocate new acreage, not to speak of even more delicate tasks such as tweaking the country’s (oftentimes outdated) 1955 Petroleum Code.